From Gutenberg Press to Social Media: Navigating the Information Paradox

07-Apr-2025

By K.K. Pathak

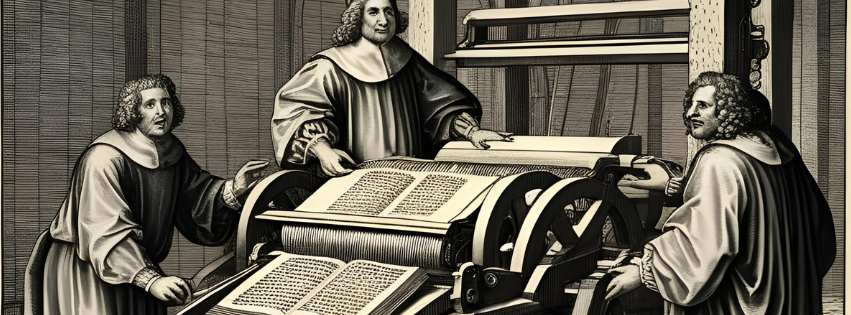

Historically, the domain of information dissemination has relied upon technological innovation. Each innovation brought new ways to share information and express ideas. One pioneering example was the Gutenberg printing press of 15th century Europe, which revolutionised information dissemination. It offered authors unprecedented freedom to connect with readers at large. As Europe’s zeitgeist was deeply influenced by the Church, much of the literature printed initially was theological, comprising religious texts, treatises and devotional works. In fact, the first major book printed in Europe was the Gutenberg Bible (Hernández, 2024). However, the printing press did not take very long to pose an existential challenge to the influence of the Church over European society. The rapid spread of novel ideas through the printing press paved the way for remarkable social changes. The Protestant Reformation, sparked by Martin Luther's writings, is an example of how the printing press facilitated the mass circulation of new teachings and ideas (Mark, 2022). Other such examples include the Renaissance and later, the Enlightenment. Large numbers of readers metamorphosed into agents of social change. Parallelly, the Renaissance effectuated the idea of Humanism which valued individual spirit and autonomy. Thus, the autonomy of the authors to choose content of choice and their agency to exercise that autonomy found newer heights. This became a key reason why their published works could spread revolutionary ideas so rapidly. There emerged an atmosphere for the authors (content creators of that era) to feel free to write what they wished and this reflected in the ways in which their readers began to think critically of the established norms (Journalism University, 2023).

Furthermore, the relationship between the readers (content consumers of that era) and the authors was such that the readers had little demand to engage in real-time dialogue with authors. In fact, the idea of “real-time” dialogue was unimaginable at that time, given the temporal and spatial barriers between the author and the readers. Once a book got published, there was little scope for the reader to engage with the author for feedback. The flow of information was thus, largely unidirectional (from author to reader). With the socio-political influence of the Church getting weakened, the relationship between the author and the reader, could grow more organically, with the agency of the author and the curiosity of the reader complementing each other.

Fast forward to the present, we today live in the Information Age. The internet, another technological innovation, has amplified information dissemination through social media to an extent that far exceeds the scope of the Gutenberg printing press. Spatial and temporal barriers between content creators and consumers seem insignificant. Social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram, driven by the internet, offer digital spaces for information dissemination where we can enjoy an online podcast by a German content creator in real-time while sitting in New Delhi (Sharma, 2024). However, the relationship between the content creators and consumers is fundamentally different from that between the authors and the readers of the Gutenberg press era. Modern digital content creation is shaped by real-time and live interaction. For the first time in history, the flow of information is no longer unidirectional, and has become two-way (Abhram, 2022). This real-time interaction occurs when content consumers use social media functionalities like commenting, reacting, reporting, blocking and hashtagging. Despite the creator’s autonomy to choose content of choice, their agency to proceed with it is now subject to the nature of interaction. While such functionalities may help counter any misinformation in real time, they birth new forms of challenge with regard to authenticity and creativity of the content. “Public opinion” now seems to be a key metric in choosing the themes of online content. To avoid real-time criticism, creators tend to make content their viewers desire, rather than what they would prefer to create. This process seems to nullify the internet's potential as a space for authentic and creative information dissemination.

The shift in the relationship can perhaps be attributed to the entry of a third agent into the equation, i.e. the market. Social media platforms have become tools to generate online revenue through monetisation mechanisms. This is done through digital revenue models, like the subscription- based model (Panjwani & Xiong, 2023). Big tech companies, operating within the market economy, ensure that this digital revenue generation process keeps thriving. Thus, market forces today influence the way information is disseminated over social media and this impacts the organic equation between the creator and the consumer. The trend pushes creators to dilute their own autonomy and produce content that keep viewers hooked, is less diverse, and eventually deprives the consumers of informative knowledge (Friedman, 2024). Interestingly, any calls for limiting the influence of big tech companies on social media through state action could possibly pave the way for government censorship and state surveillance. Thus, it could be argued that we face a paradox in the information age, where on the one hand, the internet and social media, possessing the power to democratise information, have been hijacked by the market forces, and on the other hand, state regulation, could unleash perils like social media censorship and surveillance.

We have come a long way from the Gutenberg press era. The challenges that our information world faces today, are privy only to these times and it seems logical that solutions should also be deliberated in the modern context only. While today, the market exerts a powerful influence on the agency of content creators, the fundamental human desire for illuminating knowledge remains. The future may thus hinge not on technological solutions or state control, but on fostering a critical consciousness and mass awareness that empowers people to demand/create content that transcends audience appeasement or monetary benefits, thereby causing social media to unlock new possibilities for social change.

© 2025 The Nehru Centre. All Rights Reserved.