The Ayodhya Title Dispute: Exploring The Politics of Law & Identity

01-Jan-1970

By Divya Singh Chauhan (She/her)

The Ayodhya title dispute is more than just a legal battle; it reflects India's socio-political evolution, where historical narratives, religious sentiments, and judicial processes intersect. The case, prima facie concerning the ownership of a site claimed by Hindus to be the birthplace of Lord Ram and where the Babri Masjid stood until its demolition in 1992, has been shaped by power dynamics, nationalist ideologies, and the judicial struggle to balance faith with constitutional principles.

A Battle of Narratives

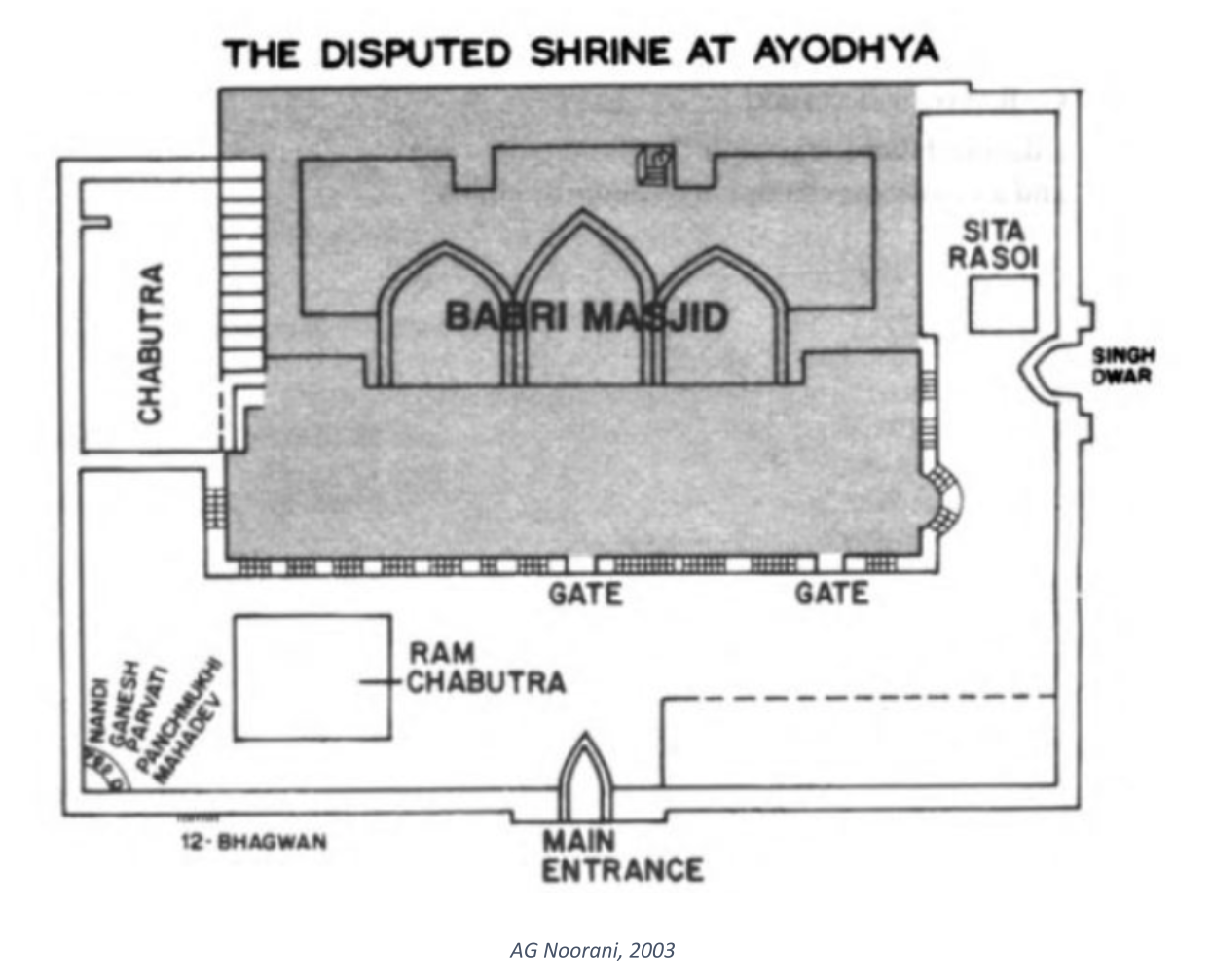

The origins of the dispute are shrouded in contested claims. While it is widely believed that Mir Baqi, a general of the Mughal Emperor Babur, constructed the Babri Masjid in 1528, the assertion that a Ram temple pre-existed at the site remains contentious. The lack of conclusive historical evidence has not prevented various groups from weaponising the past to justify their claims (Noorani, 2003). Over time, this historical ambiguity has been exploited by political actors to fuel communal tensions and solidify majoritarian narratives.

In the 19th century, the British administration capitalised on these communal divisions. The 1855-56 conflict divided the site into separate zones for Hindu and Muslim worship, reinforcing a communalised perception of the dispute (Supreme Court Observer, 2024). The first legal attempt to claim the site for Hindu worship was made in 1885 by Mahant Raghubar Das, but the British courts dismissed his plea, fearing it would incite further unrest.

Precarious Judicial Interventions

The post-independence period saw a dramatic legal escalation. In 1950, Gopal Singh Visharad of the Hindu Mahasabha filed the first case in independent India, seeking the right to worship in the inner courtyard. Subsequently, the Nirmohi Akhara and the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board also entered legal battles for control over the site (Supreme Court Observer, 2024).

A pivotal moment came in 1986 when a Faizabad district court ordered the unlocking of the Babri Masjid site for Hindu worshippers. This decision, arguably influenced by political pressures, exacerbated communal tensions and emboldened hard-line groups. The eventual demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 by Karsevaks was not a spontaneous act of faith but a calculated political manoeuvre, one that resulted in nationwide riots, deepening sectarian divisions (Pawar, 2024).

The 2010 Allahabad High Court ruling, which divided the land into three equal portions, reflected a legal compromise rather than a definitive resolution. The ruling was ultimately overturned by the Supreme Court in 2019, which awarded the entire site to Hindu claimants while offering an alternative five-acre land to the Sunni Waqf Board for a mosque (Siddiq v. Mahant Suresh Das, 2019). This verdict, while celebrated by many, can and should be criticised for prioritising faith over constitutional principles of justice and equality.

The Fallout

The Ayodhya dispute has had far-reaching consequences beyond the courtroom. The rise of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement in the late 20th century played a crucial role in the resurgence of Hindu nationalism, significantly shaping India’s political landscape. The BJP capitalised on the movement, using it as a rallying point to consolidate Hindu votes and redefine the nation’s identity along majoritarian lines.

While legally conclusive, the Supreme Court’s 2019 verdict raises critical questions about the judiciary’s role in addressing religious conflicts. By awarding the site to Hindu claimants despite acknowledging the illegality of the Babri Masjid’s demolition, the judgment set a precedent where historical grievances, rather than legal merit, dictate judicial outcomes. The Court also opened the floodgates for more such excavations and demolitions of religious monuments to happen.

The Ayodhya dispute is emblematic of India’s struggle to balance faith, history, and the rule of law. While the Supreme Court’s decision has brought legal closure, it does little to address the deeper socio-political rifts that persist. The real challenge lies in ensuring that India’s secular fabric is not eroded by the instrumentalisation of religious narratives for political gains.

Rather than viewing the verdict as an end, it should serve as a moment of reflection on the kind of pluralistic, inclusive society India aspires to be, one where historical disputes are resolved not through faith-based adjudication.

References

Noorani, A. G. (2003). The Babri Masjid Question, 1528-2003: ‘A Matter of National Honour’. Vol. 1.

Pawar, S. (2024, September 27). The Statesman.

Siddiq v. Mahant Suresh Das, (2019) SCC OnLine SC 1440.

Supreme Court Observer Archive. (2024). Ayodhya Title Dispute. Retrieved from https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1915/3/A1993-33.pdf

© 2025 The Nehru Centre. All Rights Reserved.